MHS Phone Ban

By: Phoebe Bakeman

2/6/26

When Martin Cooper made the first-ever cell phone call on the streets of New York City, with a phone affectionately and accurately dubbed “the Brick,” he almost certainly got a few weird looks from passers-by. What was this man doing standing on the sidewalk, talking through a 2 ½ pound chunk of metal to someone who wasn't there?

Today, the personal cell phone has become so ubiquitous, so all-encompassing, that what isn't there often takes precedence over what is; sometimes the digital supersedes reality. In schools, this can have its consequences.

The National Institute of Health performed a study, examining how well people could execute a task when they were distracted (such as by phone notifications) versus when they weren’t.

According to this study, even a 3-second distraction, such as checking one's texts, lowers a person's rate of accuracy at a given task. This means that when students have their phones on them while doing work or taking notes or just talking with their friends, each time they look at it their brains must switch from one thing to another, losing important seconds of active recall. Because of this, phones, which promise instant connection to anything you might need connecting to, have been linked to high levels of distraction and disconnection in the classroom.

According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of teachers report cell phone distraction being a “major problem.”

At Montpelier High School, teachers noticed this phenomenon showing up in classrooms: students were distracted according to Principal Gingold. “There were challenges around instruction,” he says.

Students were less focused, and less likely to complete assignments in class. MHS Staff “didn't feel comfortable battling students over phones.” We had cell phone trees to combat these problems, but it fell to the responsibility of each individual teacher to enforce them, and many went unused. So, in May 2024, as other high schools such as Harwood decided to go phone-free, our school began to consider it.

During the 2024-25 school year, Principal Gingold, Vice Principal Therrien, and the cell phone committee gathered data and presented their proposal to the school board.

This year when students entered their classrooms, we no longer had our phones in our back pockets. We started out the year with a system of glass boxes for upperclassmen, and carts with individual paper files for each lower classman to put a phone into.

Recently the carts–which were a bit of a hassle; were replaced with taller carts, with open compartments for the phones. Gingold says the system is an ever-evolving one, but that teachers have already noticed marked improvements in school culture.

They have seen “less distraction, in a way, from a social and academic place,” Gingold says. Less distraction from school, and less distraction from socializing as well. “I do see less students eating by themselves on their phone,” he continued.

Student opinion on the phone policy is also generally positive, with, again, some qualms over how phones are stored.

One student, Isabel Moorman, reports that she's noticed more face to face interactions, and that “lunchrooms are louder, because people actually talk to each other,” rather than scrolling.

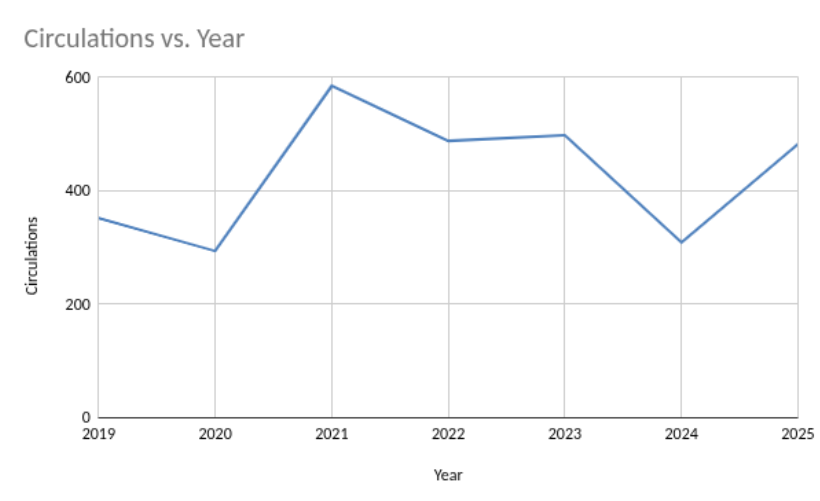

Physical books are also being appreciated more. Mrs. Monmaney, the librarian, says that she has seen a significant increase in books checked out this year, as compared to the past five years.

The new phone system is constantly changing, but with a law being implemented next year requiring all schools in Vermont to go phone-free, it's likely to stick around. Phones have come a long way and drastically shifted school cultures in just a matter of decades.

Gingold wants to emphasize that the school is not against the phones themselves, but the distraction and stress they bring to students.

The goal is not to “kill technology,” but “trying to reign it in a better space for students and adults,” he says.

Chart on MHS library circulation, courtesy of Sue Monmaney